Anna B. McCoy is the daughter of noted painter John McCoy and Ann Wyeth McCoy, and the granddaughter of N.C. Wyeth. As her cousin Jamie Wyeth often remarks, “everyone in the family paints except the dogs.” Anna B. studied painting and drawing with her aunt, Carolyn Wyeth, and later at Bennett College in Millbrook. Anna B. has quietly established her own reputation in Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maine, where her subjects tend to be personal, introspective and exquisitely evocative of time passing.

2014 Tronies and Still Lifes

"Time-worn and well-used (mostly) objects and people populate the paintings of Anna B. McCoy. Her re-invention of a type of painting popularized by Rembrandt and the Dutch baroque—the tronie—is far more than an antiquarian enterprise in this age of “selfies.” McCoy’s paintings of friends and family recall the long tradition of such explorations of the human face from Leonardo’s late in life self-portrait drawing to Rembrandt’s self-portrait etchings throughout his life and more recently in the work of David Hockney, Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, and, especially, Elizabeth Peyton’s small-scale heads of friends and celebrities. McCoy’s approach, however, is uniquely her own, and Dandelion, for example, exhibits an endearing, self-deprecating humor, comparing her own tightly curled hair not just to the ubiquitous flower, bane of bourgeois suburban lawns, but to its final, fragile state of impending dissolution just one breath away.

McCoy’s choice of the tronie is significant. An archaic term, it designates works that are different from portraits that typically would have been commissioned by the sitter or a patron. Tronies, as understood by Rembrandt, Vermeer and other painters of the so-called “Golden Age of Dutch painting” were anonymous likeness of actual persons whose faces could be seen to express certain temperaments or moods—sadness, humor, introspection, surprise, as well as other, less legible states of mind. Informal, spontaneous or tightly controlled, and revealing of the artist as much or more so than the subject, McCoy’s tronies do what straight photography is far less capable of; they reveal states of psychological being—the artist’s and her subjects’– and the interplay between artistic process and emotional disclosure, largely through the artist’s choice of what to include or ignore, emphasize or eliminate.

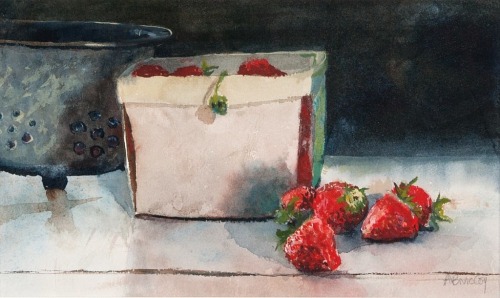

McCoy paints what she sees–family, friends and familiar objects. Both faces and still life carry intimations of time passing. And still life, as conceived by McCoy conveys distinct personas, often becoming portraits in absentia, and tronie-like in their personalities and specificity. Her still life paintings, like the tronies, are unusually simple and uncluttered; disparate flowers, fruit, vegetables, plates, utensils, glassware and other common objects are placed on tables, shelves or other furniture, usually in shallow, often indeterminate, background spaces. While the suggestion of casualness and informality prevails, it becomes apparent that McCoy’s interest lies in the subtle, almost imperceptible tensions evoked by the space between objects enhanced by unexpectedly rich colors bouncing off each other in the reflections of a glass, plate or polished metal. Edges tend to be softly modeled, light shimmers in dark recesses; brush strokes caress objects with an ineffable gentleness, quiet and reticence.

That said, both the tronies and still life paintings have intense, activated and highly worked surfaces. We are aware always of her unusual, flickering brushwork that enlivens every form, different from but acknowledging such nineteenth century American precursors including Raphael Peale, Frederick Peto, and William Michael Harnett. Every mark is just as present as the object it describes, maybe more so. In Cuban Cigar, a wisp of smoke from the lit cigar not only implies proximity to an absent but nearby smoker; it conveys a sensory world of simple pleasures—brandy, brie, human indulgence–in which even the air is tangibly “there” in the form of curling smoke deftly rendered through a brush lightly dragged, a finishing gesture to ignite the spatial relationships among objects. It is these inflected, complex, sincere, honest, painterly surfaces that convey McCoy’s own intensity and irrepressible spirit, her devotion to what she sees and knows well and intimately; analogues to life and being adamantly alive in the present.

Upon further inspection, McCoy’s dandelion hair is, then, a tousled bouquet to her own continuing presence as a painter and a fist clenched against the inevitable dark. And, as one of her aging tronie sitters, I appreciate being described in terms of McCoy’s infectious optimism for “possibilities,” even if Anna B and I don’t know or much care what those might be–given, as the saying goes, the alternative."

– Christopher Crosman, Former Director of the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine; Founding Chief Curator of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas